Decision-making

Control Measure Knowledge

Commanders should use decision-making processes at all incidents to carry out the responsibilities of the fire and rescue service. This control measure predominately applies to commanders but could also be used by any other decision makers on the incident ground.

Decision-making does not only happen at the incident ground; decisions are also made in fire control and by other agencies. It is critical that all decision makers are aware of this and the impact that each can have on others.

Decision-making is essential to the development and implementation of an incident plan. An incident plan requires decisions such as:

- What will be done

- How it will be done

- In what order

- With what

- Who will do it

Decision-making is a fundamental command skill that can have far-reaching consequences. The ability to make sound decisions, based on the hazards presented by an incident, which can be dynamic and time-pressured, requires accurate situational awareness. Sound decisions lead to safe, effective and assertive incident command.

If a commander is unable to make sound decisions this will affect all aspects of their command, for example:

- Health and safety

- Incident management

- Confidence and trust in their leadership

- Situational awareness

- Interpersonal relationships

- Teamwork

- Interoperability: co-operation, co-ordination and communication

- Confidence

- Personal resilience

Decision-making, like any complex skill, needs practice and understanding. Fire and rescue services should ensure they prepare commanders, by providing ample opportunity for them to practice and develop their decision-making.

Fire and rescue services should foster an organisational, operational and learning culture that encourages and empowers commanders to make appropriate and effective decisions. The aim should be to instil confidence in commanders to share their experiences, and to value the lessons learned. Fire and rescue services should develop their commanders by testing their personal resilience and decision-making under pressure.

Commanders should consider using the ‘Stop, think’ technique. This encourages pausing before acting or speaking, promoting careful consideration and reflection on the potential consequences of one’s actions. It is often used in the context of decision-making or problem-solving to avoid impulsive or regrettable choices or response to the situation.

Commanders should draw upon any previous operational experience and knowledge they have, along with situational awareness. Commanders need to recognise and share the fact that they might not immediately know what to do. As a result, they should consider making use of all available resources, as they may have the right knowledge and expertise to assist with decision-making and problem-solving. Resources may include personnel, other emergency responders or external organisations.

Commanders make decisions throughout an incident. These include:

- Identifying and assessing all hazards and risks

- Selecting the most appropriate control measures

- Considering the benefits versus risk of those control measures

- Taking into account any time constraints

- Identifying and prioritising objectives

- Deciding tactical priorities

- Developing and communicating a plan

- Active monitoring

Decision-making strategies

There are a number of decision-making strategies that commanders may use to reach decisions. They can be broadly grouped into two main types:

- Intuitive decision-making, which may include conditioned processes and recognition primed decision-making

- Analytical decision-making, which may include rule selection, option comparison and creating new solutions

The difference between the two main types is the time and effort it takes to make a decision. Intuitive decision-making is fast and invoked without consciously thinking. It may be driven by cues and clues that can automatically and directly trigger a decision or response. Analytical decision-making is consciously done and takes time and effort to do, as it involves developing and comparing a number of options based on knowledge, understanding and past experience of the situation.

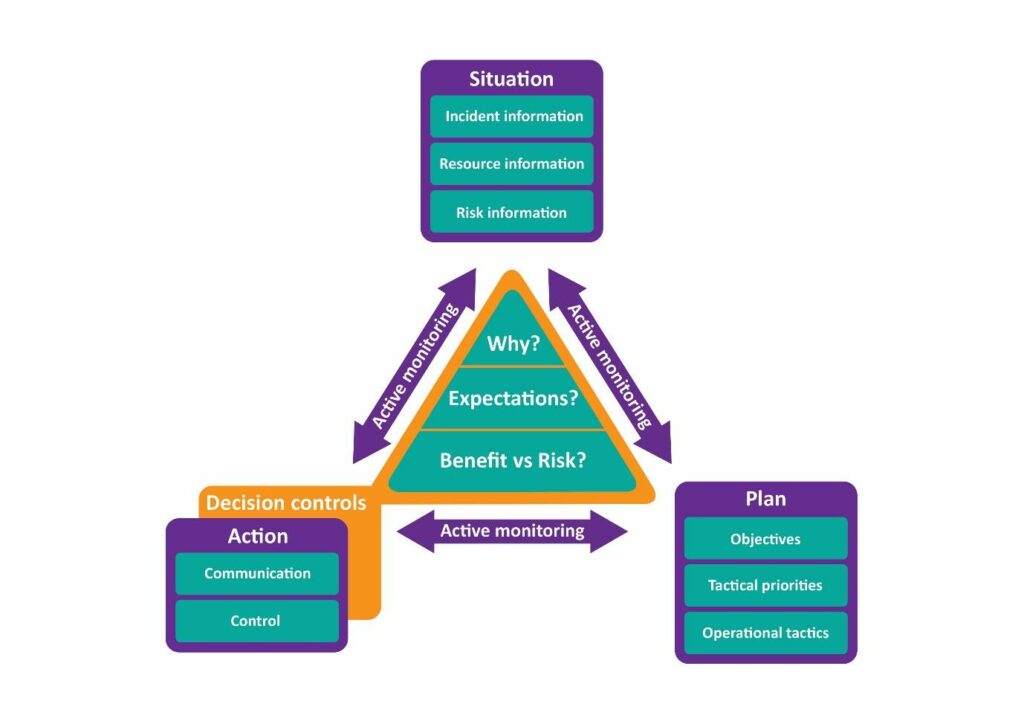

Decision control process

Commanders are accountable for the decisions they make. They should be able to provide justification for what they decided to do or not to do, and why. This is supported by the use of the decision control process (DCP). The process also assists commanders to mitigate against the likelihood of falling into a decision trap.

The DCP is scalable. It can be applied to basic decisions made on the incident ground for a task or problem. It can also scale up for use in planning the resolution of an entire incident. It complements the JESIP Joint Decision Model (JDM) for multi-agency decision-making, particularly for assessing risk and developing a working strategy.

Evidence from incidents shows that decisions are not always made in a linear way, as represented in other decision-making models. The DCP recognises this to support practical decision-making at an incident.

Under some circumstances, decision makers will respond rapidly and directly to an element of the situation, moving from situation assessment to action. This may happen when a cue prompts an intuitive decision. The DCP takes account of the way people naturally make rapid decisions. It presents some safeguards against potential decision traps. It also accounts for the slower and more reflective analytical type decision processes where plans are explicitly formulated.

The way an individual will make a decision may not be consciously selected. It depends on a number of factors related to the incident, perceived and actual time pressures, and the command role adopted. For example, a senior commander planning the resolution of a large-scale incident may be more likely to reach a decision using an analytical process. However, a commander who is first in attendance at an incident where there is a threat to life is less likely to use this type of process and more likely to use intuitive decision-making.

The process consists of four stages that are actively monitored. These are:

- Situation; incident intelligence

- Plan; based on situational awareness

- Decision controls; rapid mental check that decision is appropriate and safe

- Action; implementation of plan

Figure: Decision control process

Figure: Decision control process

Commanders should actively monitor and evaluate the situation and ensure their plan remains suitable and is making progress in accordance with expectations. Operational assurance arrangements can aid commanders in maintaining accurate situational awareness and confidence in their plan.

Situation

Commanders base their decisions on the way they interpret a situation. Good situational awareness is key to understanding the situation in a coherent way and helps to predict likely developments. By assessing the situation, the commander can understand the current characteristics and details of an incident and consider the desired outcomes.

Commanders should continually be assessing the situation to support an accurate awareness. They should gather relevant information whilst making the best use of the time available, including:

- Incident information:

- The current situation

- What led to the current situation

- How the situation might develop

- Resource information:

- The available resources

- The resources required to deal with the current situation

- What resources will be required, based on the expectations of how the incident will develop

- Risk information:

- The hazards

- Who is at risk

- What is at risk

- What control measures can be used

- What the potential benefits of a course of action are

Commanders should identify the resources currently available, and those likely to be required, to deliver a safe and effective incident plan. Appropriate internal and external resources should be requested via fire control in a timely way; fire control should be regularly updated on availability and predicted length of deployment. The time from request to arrival should be considered when developing incident plans, and available resources should be deployed effectively at all times.

For further information refer to:

- Additional resources

- Specialist resources

- Specialist advice

- Identifying the need for enhanced logistics support

- National Resilience: Provide enhanced logistics support

Plan

After assessing the situation, the commander should form a plan. They should understand the current situation and their desired outcomes. From this they can identify their objectives and develop an incident plan.

The incident plan may include:

- The incident objectives and goals

- The tactical priorities

- The operational tactics, including operational procedures

- How personnel are going to achieve the operational tactics

- Whether specialist assistance will be required

- What equipment will be required

- The location for the operational tactics to take place

- The expected outcomes and timings

- Contingency arrangements

The incident plan should be regularly reviewed and updated based on active monitoring of how effective it is delivering the expected outcomes. Active monitoring should be used to evaluate the situation to ensure the plan remains suitable and is making progress in accordance with expectations.

The incident plan should be adapted in accordance with changes to the situation if there are unexpected developments in the incident.

Decision controls

The decision controls represent a safety mechanism to guard against decision traps within the DCP. They build in reflective thinking ahead of decisions being made and get commanders to ensure they understand:

- Why they want to make the decision:

- The goals it links to

- The rationale

- What they expect to happen:

- Anticipate the likely outcomes of the action, in particular the impact on the objective and other activities

- How the incident will change as a result of the action

- What cues are expected

- Whether the benefits are proportional to the risks:

- Consider whether the benefits of proposed actions justify the risks that would be accepted

Action

This involves implementing the decisions that have been made. Wherever feasible, decision controls should be applied before this phase, or as soon as possible afterwards. This applies whether decision makers move to Action from Plan, or directly from Situation. The two elements of this phase are:

- Communicate the outcomes of the decision effectively, by issuing instructions and sharing risk-critical information; this may also involve providing updates on the situation, on progress, or other information about what is happening at an incident

- Control how the activities are implemented to achieve the desired outcomes; this may require delegating responsibility where this will help increase or maintain control

Active monitoring

The commander should be actively monitoring and evaluating the situation, including progress being achieved against what is expected, to ensure their situational awareness remains accurate.

Commanders should consider whether their tactics or incident plans are suitable, sufficient and safe; they should consider and question any areas of uncertainty, especially where they have made assumptions. Operational assurance arrangements can aid commanders in maintaining accurate situational awareness. For further information refer to Corporate Guidance for operational activity: Operational audits.

Progress information should be considered, including:

- Actual progress; what progress has actually been made

- Expected progress; how does this compare to the expected progress

- Predicted progress; what further progress is predicted

- Comparison of what happened to what was envisaged to happen; what is now predicted

Decision traps

Decisions made by commanders may be subjected to a number of decision traps. A decision trap can be described as an errant thought process that can lead to an incorrect decision being made; this may result in a situation worsening. The intuitive decision-making process is subject to biases; this process can be affected by stress that can impair a number of thought processes.

Uncertainty is a primary stressor for commanders of which there are two main types:

- Intra-incident uncertainty: uncontrollable characteristics of the incident; sources of uncertainty can include:

- Too much information

- Insufficient information

- Extra-incident uncertainty: characteristics of the command system beyond the incident and outside of the control of the commander; sources of uncertainty can include:

- Insufficient depth of understanding about the roles of others

- Limited provision of information about inter-agency arrangements

Decision inertia is one type of decision trap; commander uncertainty has been linked to this redundant deliberation to decide to take action or not because of anticipated negative consequences.

There are a number of other types of decision traps that may make decisions in the operational context less effective, including when:

- A decision does not fit with the objectives, tactical priorities or incident plan

- A decision is made on the basis of part of the situation, such as a cue or a goal, while not taking account of the overall picture

- A decision is based on the wrong interpretation

- There is decision aversion

- There has been a failure to actively monitor and review the situation

Further information on the decision-making categories, decision traps and decision inertia can be found in Incident command: Knowledge, skills and competence.

Professional judgment

Professional judgment can be defined as:

The combination of personal skills and qualities with relevant knowledge and experience, to form opinions and make effective decisions

Professional judgment can be exercised by commanders when using decision-making processes. Professional judgment is an enabler for the commander to make decisions including for situations that are not explicitly covered by tailored guidance, policies and procedures, or if explicitly adhering to tailored guidance, policies and procedures may have a negative outcome.

Joint decision-making

The JESIP Joint Decision Model (JDM) was developed to help commanders bring together the available information, reconcile potentially differing priorities and then make effective decisions at multi-agency incidents.

Decision-making at an incident ground may also be carried out by other responders. At multi-agency incidents the JESIP JDM is the process that emergency responders have agreed to use for joint decision-making.

In addition to the fire and rescue service DCP, the JDM aims to determine:

- If there is a common understanding and position on the situation and response held by the multi-agency team of commanders

- If the collective decision is fit for purpose for each of the commanders

Figure: JESIP Joint Decision Model

The DCP supports the JESIP JDM. Commanders use the DCP to develop their incident plan, which will then be shared with other agencies when applying the JDM. Agencies will jointly agree the multi-agency objectives, with each having an understanding of their role in achieving these.

These multi-agency objectives will need to be translated into actions and incorporated in each service’s incident response plan. Fire commanders will consider these collective objectives, and consider the tactical priorities and operational tactics required, integrating them into their incident plan using the DCP.

Decision logs

Commanders are accountable for the decisions they make. They should be able to provide justification for what they decided to do or not to do, and why. Appropriate records should be kept at all incidents to log key events, critical decisions and the thinking behind the actions taken.

The method of recording and amount of detail will depend on the size and scale of the incident. For smaller incidents it may be enough to use informative messages, tactical modes and records made in notebooks. Records, such as formal decision logs, should be more detailed for large or complex incidents.

A decision log provides:

- An accurate ‘at the time’ record of decisions made, including those where no action is taken

- An audit trail of decisions, along with the reasons for making them based on the information available at the time

- A record of new information or changes in the situation

- A record of risk-critical information from other services or agencies

- A way of helping the handover between commanders

It is important to record the rationale behind each decision. This will help explain why the decision was made, to enable effective review and also help those who may examine the decision-making process in the future. A decision log should record actions which influence the incident plan, although is not designed to record every action taken. If there is any uncertainty over how important a decision might turn out to be, it should be recorded.

If this information is not recorded, post-incident debriefs will not have a decision-making audit trail to review. This may limit the lessons learned from an incident and may not provide effective feedback to aid operational improvement. Decision logs may also form part of the evidence in the event of an investigation.

Command decision logs should not be confused with an individual’s contemporaneous notes, which can be written by any fire and rescue service employee to capture information relating to an incident.

Operational assurance

Operational assurance arrangements can inform learning, training and development of internal policies to assist with and improve decision-making. This can also be used following a multi-agency incident, to improve interoperability and identify potential joint training opportunities. For further information refer to Corporate Guidance for operational activity: Operational audits.