Planning

A casualty-centred plan should be based on situational awareness of the casualty and the mode of transport. All casualties should be considered to have potentially life-threatening and time dependent health conditions, and be extricated to a place of safety as soon as possible with an appropriate level of casualty care.

The plan should be communicated to the team, and feedback from the team should also be considered. The plan will determine the appropriate approach, considering appropriate glass management, space creation and access, determining what is necessary for the safe and timely rescue of the casualty.

All responding agencies should work together to develop a bespoke casualty-centred extrication plan, with the primary focus of minimising entrapment time.

Independent of actual or suspected injuries, casualties should be handled gently, and dignity maintained where possible. A focus on absolute movement minimisation is not a justified single approach and should be balanced against the speed of access and casualty extrication.

Casualties should be prioritised based on the severity of their injuries, overall condition, and the circumstances of the incident. If immediate medical assistance is not available, and the casualty can be safely supported, personnel should take proactive steps to improve casualty outcomes. The medical needs should guide the extrication process and, if a safe environment can be provided, personnel play a crucial role in ensuring that the incident progresses to a point where a safe final extrication can be achieved, before medical responders arrive if required.

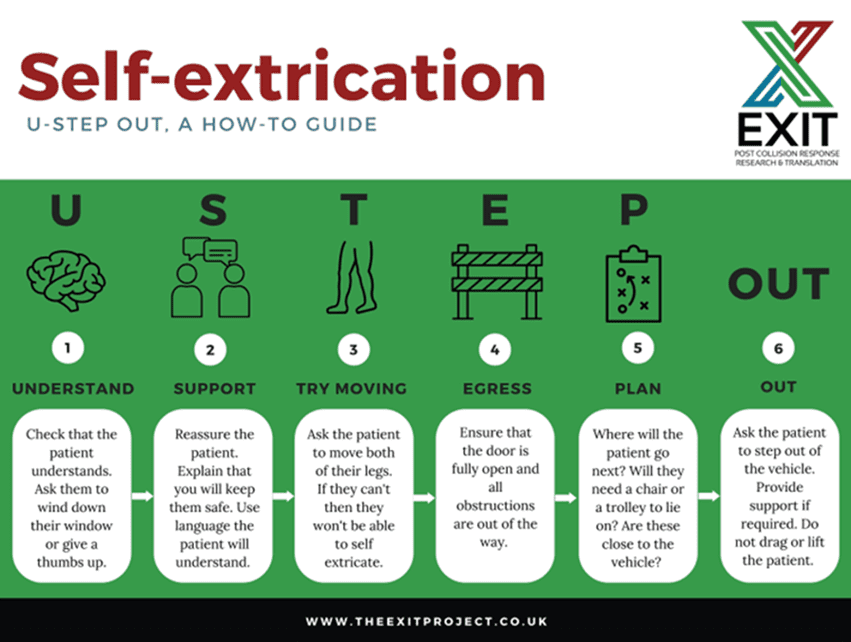

Self-extrication or minimally assisted extrication should be the standard ‘first line’ extrication and should always be considered in the first instance wherever possible. If this has been identified through a multi-agency risk assessment or by fire and rescue service personnel following the U-STEP OUT principles, then this should be applied.

Figure: Cue card describing the U-STEP OUT self-extrication process, courtesy of the EXIT Project

The U-STEP OUT principles may not be suitable if one or more of the following contraindications are present:

- An inability for the casualty to understand or follow instructions

- The casualty is unable to stand, or it suspected they would be unable to stand, either due to injury or another condition, for example:

- Suspected pelvic fracture

- Impalement

- Suspected or confirmed leg fractures

- Signs of dizziness or confusion

The removal of any physical entrapment should be prioritised, to ensure the casualty can be removed from the mode of transport if their medical condition rapidly deteriorates.

Personnel should be aware that the decision to perform a rapid rescue of a casualty, as determined by their medical condition or external factors, could be made at any stage of the rescue.

Casualty-focused extrication

There should be a focus on the casualty during their extrication, with the following principles applied if possible:

- Communicate with casualties using their name if known, to:

- Explain what is happening during the extrication

- Reassure them about their own wellbeing; ongoing, regular reassurance may have a positive impact on the casualty’s mental health

- If appropriate, reassure them about the wellbeing and safety of others, including companion animals

- Provide an ‘extrication buddy’; this is a member of the emergency services team who is dedicated to communication, reassurance and explanation to the trapped casualty

- Allow the casualty to communicate with family or friends if safe to do so

Requesting additional resources

Requesting additional resources at the earliest opportunity should lead to reduced rescue and on-scene times. Resources could include:

- Additional or specialist medical assistance

- Heavy lifting equipment

- Additional or specialist rescue equipment

Consideration of these requirements should be given while en route to the incident, based on information obtained by other responders already on-scene, or information gathered by fire control. This may also include information provided by the manufacturer of the vehicle through an automated system of alert, such as SOS or eCall system.

Consider mode of transport relocation

Consideration should be given to relocating a mode of transport; this could be either the one containing the casualty or another one involved in the incident. The mode of transport may need to be moved away from another object, obstruction or hazard. Carrying out this may:

- Improve safety

- Reduce rescue times

- Provide better access to the casualty

However, this action may not be required, or may not be possible. If the mode of transport is to be relocated, this approach should be used in conjunction with advice and monitoring from medical responders. The decision also needs to be based on the time it will take to relocate the mode of transport, as part of the overall time to rescue the casualty.

Initial access

Initial access to the mode of transport may be required to provide stabilisation; this may include:

- Applying its parking brake (also referred to as a handbrake)

- Selecting an appropriate gear for the transmission type

- Isolating its engine

- Temporarily using other methods to reduce the risk of it moving; if safe to do so, this could include personnel bracing the mode of transport

Initial access may also be required to provide urgent medical assistance to a casualty, which may be achieved by opening a door or rear hatch, or by breaking a window or sunroof. These actions should not be delayed by implementation of stabilisation unless the mode of transport is in an unsafe position. For further information refer to Transport – Using tools to access modes of transport.

For incidents involving a large goods vehicle (LGV) or heavy goods vehicle (HGV), a clear working area should be established around it to allow the use of mobile platforms, from which personnel can work. A platform should allow for personnel to work at the same level as the casualty, without having to encroach on the minimal space available within the driver’s compartment. For further information refer to Transport – Accessing large modes of transport.

If platforms are used, personnel should be managed to ensure that the limited space is used effectively, and the number of personnel should be kept to the minimum required to carry out the rescue.

Stabilisation

The mode of transport may need to be stabilised, using the most proportional and appropriate method for the safety of the casualty and emergency responders. Based on the requirements of the incident, a staged approach to stabilisation may be applied, using all or some of the stages:

- Phase 1 – Initial stabilisation to allow responder access to the mode of transport, for example to provide the casualty with medical assistance, actions may include:

- Determine if the mode of transport is stable and safe to access with no remedial actions required

- Applying a parking brake (handbrake)

- Isolate vehicle to prevent it restarting or re-energising

- Applying chocks

- Applying a winch wire or ratchet strap

- Phase 2 – Intermediate stabilisation to provide a platform from which responders can safely enter and exit the mode of transport and operate rescue tools. This can be achieved using chocks, wedges, props or ratchet straps. Absolute stabilisation is not necessary.

- Phase 3 – Full stabilisation to provide absolute immobilisation of mode of transport in situations where the casualty is impaled by an object, or if the mode of transport is in a precarious position. This involves using additional equipment to stabilise a mode of transport, such as:

- Winches

- Cribbing

- Struts

- Hydraulic or pneumatic stability equipment

- High or low-pressure lifting bags