The response to all multi-agency incidents should be based on the JESIP principles; these are essential as the foundation for responding to a terrorist attack. The exact response will be determined by the type and scale of the attack.

The JESIP M/ETHANE model should always be used to share information as it provides a common structure for on-scene responders and control rooms. The initial M/ETHANE message from on-scene responders, who may be unaware of the nature of the incident, will provide an early scene assessment. This should be used by incident commanders to co-ordinate an effective response.

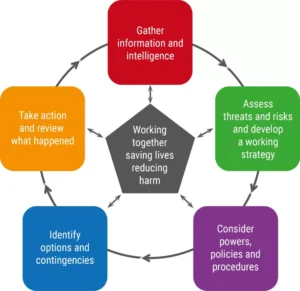

Effective response arrangements and decision-making are underpinned by the JESIP principles for joint working, as defined in the JESIP Joint Doctrine: The Interoperability Framework. Joint decision-making should use the JESIP Joint Decision Model (JDM).

Figure: Diagram showing the JESIP Joint Decision Model (JDM)

Identification and declaration of a marauding terrorist attack

Any emergency service can report a suspected terrorist attack or marauding terrorist attack (MTA) to the police. Taking this step should include the immediate sharing of all relevant information with other emergency service control rooms via a tri service communication link.

When the police declare that the incident is an MTA, they should immediately share this classification with other emergency services. Any delay in making or sharing an MTA declaration will affect the speed and effectiveness of an appropriate response.

The police declaration of an MTA should include details about the attack methodologies used, threatened or suspected. This essential information needs to be communicated to all emergency services to ensure there is appropriate and proportionate mobilisation of responders, as well as a joint understanding of risk and shared situational awareness.

Indications that a terrorist attack or marauding terrorist attack is occurring may include:

- Reports of terrorist attack methodologies being used or threatened:

- As multiple calls into control rooms

- Through social media surges

- At iconic sites

- In crowded buildings or places

- Against individuals or groups of people

- Against security staff, military personnel or emergency responders

- Aggressive, threatening or extremist behaviour

- Attackers actively and deliberately seeking out new victims

- Multiple malicious attacks:

- At nearby locations or spread across a wider area

- Simultaneously, in quick succession or over a more extended period of time

Responsibilities of agencies

The police will lead on the overall response to a terrorist attack or MTA; they will deploy appropriate resources to identify, locate and neutralise the threat. The police will retain overall responsibility for co-ordinating the multi-agency response. However, each agency must comply with their legislative responsibilities, including those for:

- Data and information management

- Risk management

- The health, safety and welfare of their employees

Normally the police response will be that of a geographic police force. However, if an attack takes place in the operating environment of a functional police force, they will take an active role in responding to the incident and may have primacy. The functional police forces include:

- British Transport Police (BTP)

- Civil Nuclear Constabulary (CNC)

- Ministry of Defence Police (MDP)

The fire and rescue service will retain lead responsibility for their core functions, such as firefighting, rescue and hazard management activities, as a result of a terrorist attack or MTA. The fire and rescue service may need to provide resources and equipment to deal with these core functions. This could include decontamination of casualties, survivors and emergency responders. For more information refer to Fires and other hazards: Terrorist attack.

The fire and rescue service may be required to assist the ambulance service with casualty management; this includes the treatment, removal or transfer of casualties who have been injured in the attack. For more information refer to Casualty care: Terrorist attacks.

It is foreseeable that the fire and rescue service may be required to carry out their core functions and casualty management at the same time. If this is the case, the commanders for each emergency service in attendance will need to agree priorities, based on available information and the primary aim to save lives and reduce harm.

The fire and rescue service may be able to provide information about the location, based on Site-Specific Risk Information or site inspection visits. For more information refer to Corporate guidance for operational activity – Site-Specific Risk Information.

The ambulance service retains the lead responsibility for casualty management at a terrorist attack or MTA. The priority is the rapid deployment of emergency responders, to provide immediate life-saving intervention to as many casualties as possible, within the shortest possible time. The aim is to maximise casualty survival until definitive medical care can be provided.

National Inter-agency Liaison Officers (NILOs) undergo training that enables them to liaise with and support the incident commander by acting in a tactical adviser or co-ordinating role for terrorist attacks, MTAs or other counter terrorism events. All NILOs have national security vetting at a minimum of Security Check (SC) level. The NILO network is aligned with UK Counter Terrorism Policing, with dedicated NILOs attached to each region.

Mobilisation

The multi-agency response should reflect the attack methodologies and the threat. It should consider the need for specialist and non-specialist responders, and the time it will take to mobilise them to the incident.

In preparation for such incidents, all emergency services should identify and appoint appropriately trained, equipped and competent responders to carry out key command and support functions. There should be well-rehearsed plans, which have been developed through joint training and exercises.

Communication

The JESIP principles state that meaningful and effective communication between responders and responder organisations underpins effective joint working. Communication links start from the time of the first call or contact, instigating communication between emergency service control rooms as soon as possible to start the process of sharing information.

As a priority, the police will instigate the pre-planned tri-service communication link between the emergency service control rooms. This may be best achieved by using the relevant Emergency Services Inter Control (ESICTRL) Talkgroup. The link should be kept open and resourced appropriately for the duration of the incident; it should not be terminated until all parties agree that it is appropriate to do so. This line of communication should be resilient, with its use being practiced and tested regularly.

All communication between agencies should be free from acronyms and use plain language. The information shared should use a M/ETHANE message:

Figure: Diagram showing the JESIP M/ETHANE model

Co-location and co-ordination

Effective command requires multi-agency co-location at a number of points at or near to the incident. Any location used by the emergency services should be checked and secured against potential threats, including secondary devices or discarded improvised explosive devices (IEDs), with protection measures implemented where applicable. The security of designated locations should be continuously reviewed, with any changes communicated to the commanders for each emergency service in attendance.

Emergency service locations

Some sites have predetermined emergency service locations, although their appropriateness and security would need to be reviewed before they are used for a response to a terrorist attack.

Rendezvous point (RVP): The on-scene police commander should determine the location for the RVP, having taken into account the needs of all emergency services that will be in attendance. The RVP should:

- Be located in the cold zone

- Be easy to locate

- Enable the rapid deployment of resources and assets to the scene

- Be of suitable size and configuration to meet the operational requirement

- Be regularly reviewed by commanders

As a matter of priority, the police control room should provide the ambulance and fire control rooms with details about the location of the RVP for the initial response. Fire control personnel should receive this information, or request it from the police control room, and use it when mobilising resources to the incident.

Forward command point (FCP): Commanders are responsible for identifying a suitable FCP for the deployment of emergency service responders. The FCP should:

- Be located in the cold zone

- Be regularly reviewed by commanders

There may need to be more than one FCP, depending on the attack methodologies that may be multi-sited. Even though the location of FCPs may change during an incident, it is vital that command and control structures are maintained to ensure co-ordination of the incident and the safety of emergency service responders.

If there is insufficient time to establish an FCP, emergency service responders may need to be deployed following the agreement of a joint understanding of risk.

Tactical co-ordinating groups (TCG) and strategic co-ordinating groups (SCG): Some command roles will need to attend meetings of these groups. For more information refer to:

- The JESIP Joint Doctrine: The Interoperability Framework

- Incident command: Knowledge, skills and competence – Levels of command

Control rooms: Where possible and appropriate, co-locating representatives from the partner agencies within a control room can help with effectively sharing and co-ordinating available information

Counter Terrorism Police Operations Room (CTPOR): If established, suitably vetted NILOs from the ambulance service and fire and rescue service should attend to support the police CT Commander. Tri-service attendance at the CTPOR will ensure:

- Appropriate intelligence and information sharing between partner agencies

- Co-operation and understanding amongst agencies on matters of organisational capacity, capability and command

- A reduction in risk to emergency service responders and the public

Counter terrorism arrangements for the devolved administrations may vary; for example, CTPOR arrangements.

Fire and rescue service command

At a terrorist attack, the incident commander should be appropriately trained and competent, as they are responsible for undertaking an ongoing joint understanding of risk and decision-making on the deployment of fire and rescue resources.

Some fire and rescue services appoint a NILO to co-ordinate a specialist response, but this role may be held by the incident commander.

The incident commander will initially operate from the RVP, moving forward to the agreed and identified FCP at the appropriate stage unless they devolve responsibility to a supporting commander, such as an operations or sector commander. Fire and rescue service commanders should be identifiable by wearing a suitably marked tabard or other means.

Those performing command roles may need to wear a properly-fitted enhanced level of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, this can be reviewed and scaled down if appropriate, based on the nature of the attack methodologies and the joint understanding of risk undertaken with the other emergency service commanders.

It is likely that the fire and rescue service incident commander will need to establish an appropriate command support function. For more information refer to Incident command – Command support function.

Fire and rescue services need to ensure they are represented at all meetings and briefings; if the incident commander needs to remain on-scene, this role may be assigned to a NILO or a member of the incident command team.

The assigned fire and rescue service representative attending an off-site meeting needs to be fully briefed and empowered to make decisions on behalf of their service. If the incident commander remains on-scene, the communication between them and the assigned representative needs to be robust.