Data and Business Intelligence Guidance

Who is this guidance for?

This guidance on the use of data in informing a CRMP from development to implementation is for those tasked with leading, managing and developing community risk management plans (CRMP) for UK Fire and Rescue Services (FRSs). It contains a Fire Data Lifecycle that describes a best practice approach to CRMP data management.

Note: For reader ease, where the term ‘data’ is used, this also includes ‘Business Intelligence’ wherever it is relevant.

Introduction

This guidance is intended to aid strategic managers, data analysts, and others in the FRS who work with data and data sources to create a robust evidence base that underpins the CRMP.

It is recognised that

- some FRS staff involved in the creation of a CRMP may have limited experience of working with data and their sources, and so this guidance has been written to be accessible to anyone who has responsibility for developing any of the component parts of a CRMP.

- The responsibility for data collection, processing, and delivery may sit with others in the FRS, governing or partner organisations, and this needs to be accounted for within the data collation process.

- Those tasked with managing CRMP processes may not be directly responsible for generating or sourcing data, only its use within the CRMP, and therefore cross-team, cross-function, and cross-organisational working will be essential.

- The roles of data preparer, collector, analyst and CRMP manager, may be carried out by individuals or groups, depending on the size and structure of the FRS. For simplicity, this guidance describes them as separate roles, but elements of all these roles could be combined into one or more post.

It may be appropriate for an FRS to appoint a data analyst or analysts, or similar, who have a wider remit to cover all data requirements to support the CRMP and to work with strategic managers throughout all the stages of the Fire Data Lifecycle.

The CRMP Strategic Framework has been designed to show all components of a CRMP and how data should be utilised throughout the process to ensure that it is evidence-based, and intelligence driven.

It is important to note that data is not just relevant to the risk analysis component of the process but is also crucial when managing other aspects such as Stakeholder Engagement and Equality and People Impact Assessments, as the intelligence gathered needs to consider, represent, and reflect the communities and stakeholders influenced by the CRMP.

Therefore, a consistent and methodical approach to gathering data across the process will ensure:

- Accuracy so that the resulting CRMP is fit for purpose.

- A more defensible CRMP that better withstands scrutiny in the forms of internal and external governance, inspection, and public consultation.

Introducing the Fire Data Lifecycle

A CRMP sets out for how a FRS plans to mitigate foreseeable fire-and-rescue-related risk using available, but finite, resources.

The term ‘Resources’ may include people, skills, money, buildings, infrastructure, and equipment, but also includes data. Each FRS holds, and has access to a wide range of data, and can use it to help understand, plan for, and respond to community risk.

When starting to think about the content of a CRMP, it is important to know what strategic objectives should influence this, and what questions need to be answered. For example:

How do we allocate resources in the most effective manner to reduce community risk through our protection, prevention, and response activities?

The answer to this question is supported by data.

Up-to-date, relevant, and credible data can help strategic managers decide what is the right approach and advise those who make decisions about the balance between allocating finite resources and mitigating community risk. To do so, this guidance uses a Fire Data Lifecycle to provide a structure for the evaluation and use of data during the development of the CRMP.

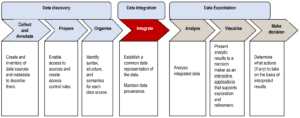

The concept of a data lifecycle was explored in research commissioned by the Chief Fire Officers Association in 2016, which used a ‘big data value chain’ approach developed by Miller and Mark in 20131.

The diagram below explored the issues involved in the:

Acquisition and storage

Preparation and cleansing

Linkage and integration

Analysis

Modelling and visualisation

Decision-making, and

Evaluation of the data.

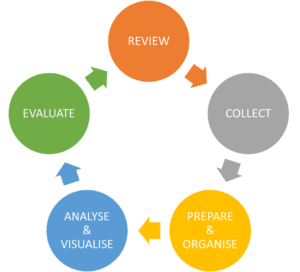

Iterative Fire Data Lifecycle

Iterative Fire Data LifecycleThe Fire Data Lifecycle starts with review then moves clockwise to the collect stage, then on to prepare and organise, followed by analyse and visualise, before ending at the evaluate stage.

The evaluate stage then provides the basis for the review as the cycle starts again.

The following sections describe in detail each step in the process.

This approach has been reviewed and simplified to help strategic managers consider how to use data as part of the development of a CRMP.

Review

All FRSs will have existing risk management plans, as they are a legislative requirement. Taking time to examine and consider the existing CRMP, and assessing its suitability and success, is an essential element of the Fire Data Lifecycle. The existing CRMP will have been subject to review throughout its life and likely has an action plan (or similar) attached to it, and this can be incorporated into this process. As detailed in the CRMP Strategic Framework, each component of the process should be evaluated, however the specific “review” stage of the Fire Data Life Cycle relates to the data used to support the CRMP.

A FRS should take time to review the outcomes and performance of their CRMP. This will provide evidence of what data was effective and can remain, and what changes are required because of learning at a local or national level.

Collect

Having carried out a review of the existing CRMP, the next stage is to look at what data is available to inform the new plan. The review will provide a reminder of what data sources have already been used and what value they bring to the CRMP. This information provides a basis for the collect stage of the lifecycle. Before looking at specific data sources available internally and externally, there are some broader principles that need to be considered when collecting data.

Granularity & currency

Not every dataset has the same level of detail, or granularity. For example, a dataset containing details of individuals who have received a home fire safety check will include data at household level, whereas Public Health data linked to influenza vaccinations could be grouped by age cohorts, or by geographical areas that include many households.

It is always worth thinking about the granularity of data and what value it can bring to the analysis and insight required to support the CRMP. In short, detailed data allows detailed analysis, but has implications in storage, and may require special governance arrangements. Coarser data is easier to store and more anonymous but may not give answers at a detailed enough level to allow targeting activities to mitigate community risk.

Also, in collecting local data, care needs to be taken about assuming that any statistics apply equally and evenly throughout the whole area. For example, an average level of employment across Birmingham, does not mean that all areas in Birmingham share that exact characteristic. Using smaller ‘areal units’ can help if they are available, but consideration should always be given to the size and constituent parts of an area and how statistics within it are reported. This is commonly referred to as the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem.

Data is collected, produced, and disseminated at varying periods. Some datasets (such as the Census) may only be collected every 10 years, which means that the data in them may not be current. It is worth considering when an update to a dataset may be available, especially if it is intended to monitor some sort of change and consider how this aligns to the timescale of the CRMP.

People or place

Consider if the data is about ‘People’ or ‘Place.’

‘People’ data can be about groups or individuals. It may not include personal data, but can, and that brings certain responsibilities (see section 5.4).

Geographic data can help to understand an area in a community. For example, data about housing stock, types of premises, and transport routes can help build a more detailed picture of an area.

When dealing with spatial data, it is important to understand how an area relates to a population, and if comparing areas, how the relative geographies match. It is possible to analyse areas of assorted sizes, with different populations, using statistical methods, but it requires expert input. A common spatial unit in UK population statistics is the Lower Super Output Area (LSOA), which can be used for relative risk comparison between areas that contain approximately 650 houses or 1500 people. Useful statistical data is commonly published at LSOA level, allowing for datasets to be brought together at the same level of granularity.2

Some geographic datasets include a Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN). The UPRN is the unique identifier for every addressable location in Great Britain. By adding the UPRN to a dataset, it enables linking together of matching records in different databases. This can provide a richer view of a single premises.

Even when place-based data does not include the UPRN, it can still be of value, and a data analyst can suggest ways in which to use it to gain useful insight. Both LSOA and UPRN are key data sources which support the Community Risk Programme – Definition of Risk benchmark to determine a dwelling fire likelihood vs consequence methodology.

Credibility, quality, and reliability

If it seems that an external data source has some potential for improving the CRMP, then it is important to think about the credibility and the reliability of the data.

|

Questions to ask With all data, consideration of its quality can be assessed by asking questions such as:

|

Data Ethics & Protection

The Open Data Institute (ODI) offers some useful advice on data ethics that should be applied to all use of data.

“Data ethics relates to good practice around how data is collected, used, and shared. It is especially relevant when data activities have the potential to impact people and society, directly, or indirectly”

The ODI goes into some detail on this topic and have developed a Data Ethics Canvas which is a useful resource. It reinforces, among other things, the need to ask the question: What is the primary purpose for collecting and using data in this process?

Where information about individuals is collected and processed, 3.

Data sharing

It is important to consider data sharing when looking to access external data sources. There must be an arrangement in place for the safe sharing of data between organisations. This can vary from an informal agreement between individuals to a more formal legal arrangement that includes a wide range of data sharing matters.

Each FRS will have someone who can advise on these matters. The Information Sharing Gateway is a good source of information and many FRS are using their service to facilitate data sharing with other public bodies.

Prepare and organise

Having established access to both internal and external data sources, the next stage in the lifecycle is concerned with data preparation and organisation.

First, appropriate data storage needs to be established. This means the use of databases to house data rather than a reliance on multiple documents such as spreadsheets, pdfs, or word documents. This means that data can be searched meaningfully, and datasets incorporated into analysis more robustly. The specifics of this will be determined by the individual FRS and data analysts who work with the data daily.

Clean and validate data

Data preparation includes cleaning. The adage ‘garbage in, garbage out’ is an apt way of thinking about data. Clean data uses consistent terminology, has no spaces in cells, no blank lines, and no duplications and so on. Clean data is quicker and easier to analyse.

For all data, there is value in knowing how, why, and when the data was collected to aid understanding. This is known as “metadata”. For example, knowing how firefighters carry out home fire safety checks could shed light on why particular fields in the dataset are not as ‘clean’ as others. If the data comes from an external source the initial data entry is not something that can be controlled, so it’s worth being aware of these points when considering collection, as it may require cleaning, which can be time-consuming.

This links directly to the next consideration in the preparation and organisation stage: data quality. It is worth working closely with data analysts to consider whether there are any data quality rules that should be followed. These may include decisions about how far back the data should go to be helpful.

It may be the case that the data, internal or external, will not be suitable in its existing format and needs restructuring. That may only come to light during the analysis stage, but where it is obvious during preparation, data analysts can advise on restructuring to avoid any pitfalls or inefficiencies in the process.

Having done all this work, the next task is to validate the data. For example, this is particularly important when using a data standard like a UPRN. Checking to see that the UPRN is the right one, perhaps by cross-referencing its use with other sources, can be time well spent at this stage, rather than discovering an error at the analysis stage and having to return to do this task again.

Finally, it is important to be strict about version control of files, especially where they are accessed by many different people in the FRS.

|

Checklist

|

Analyse and Visualise

Initial analysis

Having cleaned the data and stored in it an appropriate database, the next stage is to use database queries to begin to understand the data itself. The first stage of this is often referred to as ‘exploratory analysis’ and this can be as simple as creating tables or simple graphs of the relative quantities of elements within the data.

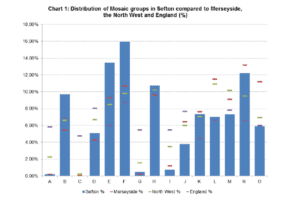

For example, if the data concerns household classifications, you may want to create a bar chart of the different groups in your area. FIGURE 2 shows an example of this for a local authority.

This initial exploratory analysis is often quite quick and easy but should never be underestimated – the goal of exploratory data analysis is to develop a deep understanding of the data available. It can often give insights into areas that require more investigation, or at least provides an overview of the intelligence contained within that dataset.

Exploratory analysis can be directed by and understood in relationship to the basic questions about risk in given areas. The questions below give basic examples of questions that can be asked, and hopefully answered at this stage. If possible or appropriate, these questions could also be asked earlier, at the collection or sourcing stages of the Fire Data Life Cycle to aid efficiency in the process of data collection.

|

Who? |

|

|

What? |

|

|

When? |

|

|

Where? |

|

Further Analysis

Bearing in mind the requirements of the CRMP, it is a good opportunity at this stage to think about how the data can support:

assumptions that may already exist

testing of new ideas

debunking ideas that have no evidence in the data

connections between data, ideas, and professional judgement, and

the identification of proxies.

This stage of the data lifecycle will require support and guidance from data analysts. While basic exploratory analysis, like using pivot tables in Excel, can be done by non-specialists, there are analytical techniques that data analysts can use to extra more value from the data. The working relationship with analysts and technical experts does not commence at this stage of the process but should be established early and continue throughout the whole CRMP process. Indeed, the development of a CRMP and subsequent data analysis requires the input of multidisciplinary teams within an FRS.

There are a wide range of software tools that can be used to analyse data, including specialist statistical packages such as (R, SPSS), data visualisation software (MS Power BI, Tableau) and Geographic Information Systems (ArcGIS Pro, Cadcorp, QGIS). Examples of software packages and their use are illustrated in Appendix C.

Specialist advice may well be beneficial with these elements, as statistical and geographical analysis can produce misleading results if not carried out correctly. It is sensible to spend time at the design or conception stage to consider what the purpose of this data interpretation is, and how it might be presented best.

| Things to consider

Data analysis should lead to insights, therefore consider:

|

Analysing more than one dataset can be useful in giving confidence in the results obtained and should always be considered if it is possible to carry out. This is known as ‘triangulation’ or ‘integrative data analysis’. There are different ways of doing this, and data analysts can suggest how to do this to help with answering the question at hand. Triangulation also assists with validation, as having more than one dataset enhances and strengthens the overall analysis.

There are many approaches to analysing data, and the tool used will also affect how the output might look. When thinking about presenting data in a CRMP, it is useful to have thought about what might best help the reader understand any discussion about identifying or mitigating community risk.

Maps are often useful ways of presenting data, to identify spatial patterns or to help support a discussion about place. Many FRS have access to Geographical Information Systems (GIS) based products such as ArcGIS, MapInfo and CadCorp. Spatial data is available from commercial suppliers such as Geographers AtoZ, or National Mapping Agencies, such as the Ordnance Survey, or other government sources such as census data, or the Indices of Multiple Deprivation.

The presentation of data within a CRMP is best considered in discussion with communications specialists. They can advise on presentation, and the style and design that can have the greatest impact.

Ultimately, the CRMP is a public document and is meant to be read and used by many stakeholders. Prior to its publication, the CRMP needs to be cleared by an internal governance process and that may dictate how the data is presented to support the overarching narrative. Establishing this at the outset is therefore important, as with planning enough time for this to take place, particularly if there are external contractors involved in any part of the data process.

|

Checklist

|

Provide advice

Data runs through every component of the CRMP process. It allows us to explore new ideas and can provide an evidence base to validate assumptions or hypotheses about community risk.

Being able to present data in simply, and with a clear explanation of how it has been derived can be a powerful tool to assist with evidence-based risk management planning.

Data informs decision-making, but those who make the decisions are not always those who analyse the data. Data is used to advise those who make the decisions about the content of the CRMP.

Consideration of the initial question asked should be at the heart of every stage of the data lifecycle. We should try to ensure that a narrative exists that explains the path from raw data to intelligence, to give those formulating policy and making decisions the full picture. When the analysis does not provide a full explanation of the situation or does not enable decision-makers to formulate a policy, then the analysis may need to be restructured or redesigned accordingly.

Checklist

|

Evaluate

It is important to remember that data should run through each component and supporting themes of the CRMP Strategic Framework. Therefore, when each theme has been prepared it is advisable to review how they have been supported by data – considering what worked and what did not work. Depending on the nature of the task and timescales involved, it may be useful to engage in a peer-review process to check the process and work undertaken. This will help to assure the process taken and mitigate the risk of the CRMP being weakened by insufficient or poor data.

At the start of the data lifecycle, the previous CRMP was reviewed to inform the start of the new version. The same process equally applies at the end of the drafting process. It is helpful to do this while the process is fresh, and the analysis team are available. The timing of this exercise may be led by wider organisational considerations and pressures, but either way, is a helpful learning process.

Through consultation and ongoing development, the CRMP will be subject to scrutiny through existing governance channels and stakeholder feedback. This will also assist with evaluating the process of obtaining and using data to assist with highlighting areas of good practice and learning.

|

Checklist

|

Appendix A – Examples of external and internal data sources

The following provides several examples of data sources that are either publicly available or could be used to prompt further consideration at a local level. This will usually require further exploration and, in some cases, agreements with partner agencies to ascertain what is available and to obtain data to support the CRMP process.

Note: Public data sources used to support the CRP Definition of Risk Domestic Dwelling Fire risk methodology are highlighted in yellow.

|

Theme of Data |

Source of Data or Intelligence |

Description |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Community |

Assisted Bin Collection – Available from Local Authorities |

Details of potentially vulnerable individuals who require assisted bin collections. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Provides a breakdown of housing stock by age, council tax band and property type. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Crime related data to assist with identifying where community risk may potentially exist. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Building characteristics such as age, energy performance and tenure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

A range of data sources linked to information that could assist with identifying vulnerable individuals. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Provides a vast amount of population linked information to assist with building community profiles. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Number of people in Lower Super Output Areas by age and gender. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government – Index of Multiple Deprivation |

IMD scores and deciles for net position and sub domain |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Provides a range of house price related data. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Provides a range of data sources linked to incidents on roads including injuries, vehicles types and casualties etc. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Socio-Economic Data Sets |

Commercially available products (such as Mosaic, Acorn, and Experian) providing socio-economic and lifestyle data linked to households and business. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Community / Geographical |

Local Risk Register – Available through Local Resilience Forum |

Highlights potential risks within a local area. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Highlights the key risks that could affect the UK. |

|

Geographical |

Identifying locations or areas where the risk of flooding exists |

|

|

|

Database and mapping of listed buildings and places. |

|

|

|

Local Authority Planning Applications – Available from Local Authority |

Provide details of current or proposed housing, infrastructure and major engineering developments. |

|

|

Geographical mapping data to assist with identifying buildings and terrain. Further information can also be obtained through the Public Sector Geospatial Agreement which details a number of additional sources of geo-spatial data such as Building Height and Road Networks. |

|

|

|

2011 rural and urban classification (RUC) of lower layer super output areas in England and Wales. |

|

|

|

Mapping to assist with identifying areas of Sites of Scientific Interest |

|

|

|

Standard Area Measurements (2011) |

Geographical area of an LSOA |

|

|

The Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN) is an identifier for addressable locations. |

Appendix B - Case Study

The Prevention Manager for Shropshire Fire and Rescue Service oversees a team who work on various aspects of prevention and can call on data analysis expertise that sits elsewhere in the organisation.

The team approached Telford and Wrekin Council to ask for access to council tax reduction data for people who are disabled. After considerable time spent discussing the data protection issues around sharing data about individuals, it was agreed with the Council to provide a monthly output of 30–40 referrals for people taken from the wider dataset of 1500 people. These people were then offered a safe and well visit.

Having built a good working relationship with officers in the Council, attention was then focused onto adult social care data, which would provide insight into individuals who receive care packages because of varying levels of vulnerability. To start the data sharing conversation, the Director of Adult Social Care was approached (who was also the Caldicott Guardian).

The Caldicott Guardian ensures that the handling of patient information complies with data protection legislation, but they also have a role in actively supporting work to enable information sharing where it is appropriate to share.

It was discovered that the Council had 1200 vulnerable people who received care packages for care in their homes. The Prevention Manager needed access to the name, address, and telephone number of people in receipt of care packages to offer them a ‘safe and well’ visit from their local fire station.

The Council was reluctant to share information about very vulnerable people, many of whom had representatives looking after their interests.

The Caldicott Guardian’s concerns centred on consent, considering that it would be a breach of data governance laws in this case to share personal data without the individual giving express consent. Therefore, initially, the Council agreed to add an option to choose a Safe and Well visit as part of a 12-month review point of the care package. However, without explanation of what a Safe and Well visit was, the uptake was low and during the first year, only 150 referrals were received.

As the relationship developed over time, the Council has agreed for the question about a Safe and Well visit to be included as part of the initial development of a care package for a vulnerable individual and not just at the 12-month review point, which was a major step forward for the referral process with the Council.

|

Learning points

|

Appendix C – Examples of FRS data analysis and illustration.

Cambridge Fire and Rescue Service use a dashboard approach to display performance data linked to community safety.

Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service have used data collected through the Incident Report System and their mobilising system to assist with building intelligence around different incident types and their impact.

This data is represented in hex maps and scatter charts using log axes, these were developed in R using ggplot.

Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service use a combination of data from ORH and Northumberland County Council in a geographical information system to identify targeted Safe and Wellbeing Visits (SWV) within each Station area. Modelling the ORH data with Exeter, Council tax band, social housing and property type data ensured they target and prioritise the premises with the characteristics that have been identified as having a close association with a dwelling fire in the highest risk LSOA for every station.

Using Unique Property Reference Numbers (UPRN) they can generate SWV jobs in their community fire risk management information system (CFRMIS). To support this process, the GIS software used to achieve this is ESRI’s ArcMap.

Bibliography and relevant links

Details about UPRNs

https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/open-uprn

Data Management

The Open Data Institute website is a valuable source of information about all aspects of data management: www.theodi.org

GDPR and Data Protection

For more information, visit the Information Commissioner’s Office website: www.ico.org.uk