Home Safety Policy Position Statement

1. Issue Identification

Fires in the home remain the leading cause of fire-related deaths and injuries in the UK. In England alone, there have been 254,030 accidental dwelling fires over the last ten years, with 1,804 deaths and 44,806 casualties. These deaths are preventable, and the UK’s ambition must be to drive the incidence of fires, fatalities, and casualties to zero.

Fire and rescue services (FRSs) play a crucial role in preventing fires in people’s homes. FRS home fire safety work reduces domestic fire risk and increases the chances that people will be able to escape if a fire occurs, limiting deaths and injuries. When undertaking person-centred Home Fire Safety Visits (also known as Home Fire Safety Checks or Safe and Well visits) FRS staff enter the homes of and engage with the most vulnerable people in their communities. They assess fire risk, install fire safety equipment such as smoke alarms, and give potentially life-saving fire safety advice to residents. These visits also bring wider benefits for health and social care services and contribute to the safeguarding of vulnerable people. FRS home safety work addresses a range of community risks and promotes the health, safety and well-being of communities.

The risk of fire has not gone away. Rising social deprivation, the increase in vulnerable populations, the growth of care at home models, and the proliferation of new technologies such as lithium-ion batteries all mean that people need to be alert to new fire risks in their homes. FRSs are increasingly pressured by stretched budgets and the need to respond to growing numbers of non-fire incidents and emerging risks, including floods, wildfires, and road traffic collisions.[1] The Government must support FRSs as they respond to a transformed risk profile in and beyond the home.

2. NFCC Position

Too many people still die in fires in the home. The Government must ensure that FRS prevention activities continue to save lives and money by taking action to support FRS Home Fire Safety Visit programmes; providing sustainable, longer-term funding for home fire safety education; supporting effective data sharing on fire risks and health vulnerabilities; and ensuring local authorities are funded to enforce compliance with smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide (CO) alarm regulations. Government action is critical to prevent fires in people’s homes.

3. Recommendations

- Governments should update the fire and rescue national frameworks for their jurisdictions to emphasise the role of the person-centred Home Fire Safety Visit as a key tool for delivering home fire safety advice consistently and effectively. The frameworks should highlight the NFCC Person-Centred Framework Guidance for Home Fire Safety Visits.

- The UK and devolved governments should make a strategic, multi-year funding commitment to support home fire safety education for the public and across key sectors in their jurisdictions. This should support national public awareness campaigns across the UK, the expansion of the StayWise education platform, and work to promote the person-centred fire risk assessment process among housing, health, and domiciliary care providers.

- The UK and devolved governments should support data sharing among relevant agencies and partners to refine the targeting of FRS home fire safety activity towards people at the highest fire risk. Governments should work with FRSs and other stakeholders in their regions to progress the development of a household fire risk stratification model that links fire incident data to health demographic and clinical data (based on the Wales Accord on the Sharing of Personal Information).

- As part of its commitment to reforming the rental sector in England, the Government should ensure local authorities have sufficient funding and capacity to inspect and enforce compliance with smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide alarm regulations in private and social rentals.

4. Supporting Evidence

Home Fire Safety Visits

Home fire safety prevention plays a key role in reducing the number of dwelling fires and reducing deaths and injuries, as well as limiting other economic and social impacts resulting from dwelling fires.

Home Fire Safety Visits were introduced by FRSs in the UK and around the world in the early 2000s and have been associated with a reduction in fires and non-fatal fire casualties. UK FRSs use Home Fire Safety Visits to offer bespoke domestic fire safety advice based on the household occupants’ characteristics, vulnerabilities, and lifestyle, as well as their living arrangements and the type of property in which they live. These visits are targeted at local households identified as being at a higher fire risk and aim to mitigate fire risk while trying to change some of the riskier behaviours that may affect or increase exposure to fire risk.

On visits, FRS staff make recommendations and provide advice to residents on how to reduce fire risk and how to stay safe in the event of a fire, and install safety equipment such as smoke alarms. The visits can also be used to assess people’s property for various health-related risks, such as an increased risk of falls, or to provide advice on health factors linked to fire risk, for example on smoking cessation, the use of emollient creams, or mental health. Where necessary, FRS staff will also deliver on their responsibilities to safeguard and promote the welfare of vulnerable individuals they encounter when entering people’s homes. Home Fire Safety Visits often involve engaging with isolated people in communities, who are known to have higher health costs associated with them if they are admitted to hospital. They therefore have positive knock-on impacts for health and social care services, including potential cost savings from referrals and earlier healthcare interventions.

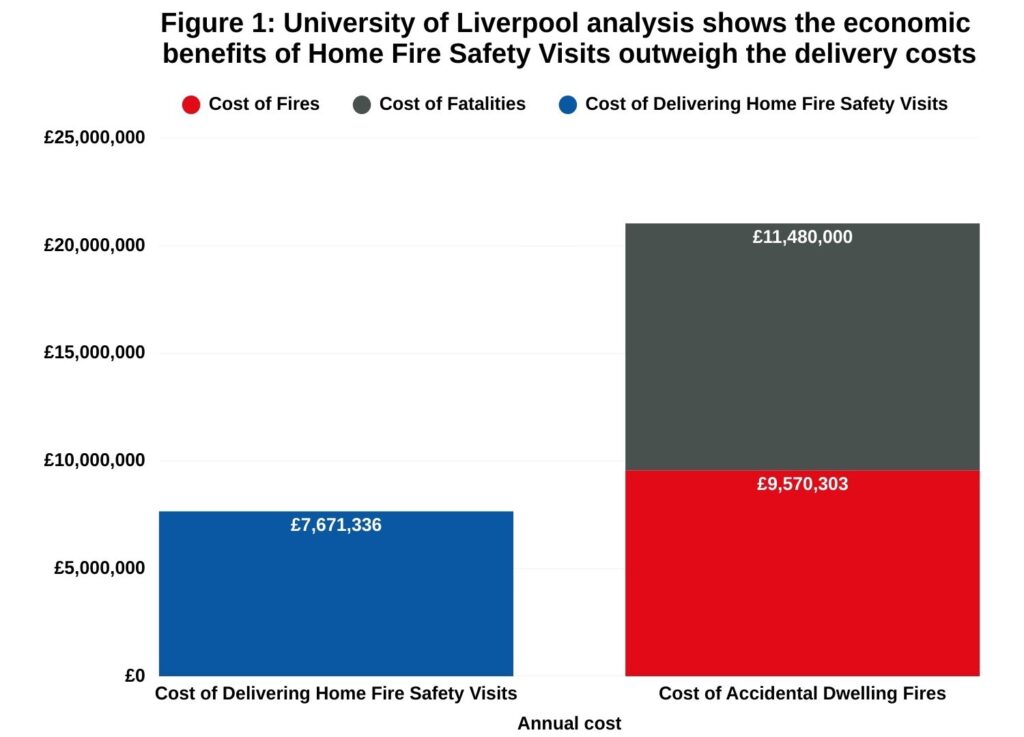

NFCC supports FRSs to deliver a standardised, evidence-based approach to their home fire safety prevention work through the Person-Centred Framework Guidance for Home Fire Safety Visits. The Person-Centred Framework centres on eight core components, or areas of advice. Underpinning the framework is the principle that risk reduction measures should be developed around the health, behaviour and wider needs of the individual and not solely the type of premises in which the individual resides, as these underlying factors can increase an individual’s exposure to fire and reduce the chances of them surviving a fire in the home. Tailoring fire safety interventions to a specific individual can also save money, as even if an intervention may turn out not to be cost effective for the population on average it may be cost effective for a certain part of the population or an individual. Research undertaken by the University of Liverpool has found that in-person Home Fire Safety Visits are cost-effective, with every £1 invested by the FRS (in staffing and equipment) resulting in savings of £2.75 from the reduction in the social, economic, and human impact of dwelling fires (these figures do not include additional monetised benefits to health and social care services).[2] The economic benefits of Home Fire Safety Visits are shown in Figure 1.

The cornerstone of FRS fire prevention work involves reducing the risk of fire in the home. Yet this is not reflected in the wording of relevant legislation, which centres on promoting “fire safety” and does not make specific reference to home fire safety. The UK and devolved governments should build on the continuing, multifaceted success of the Home Fire Safety Visit programme by strengthening the position of Home Fire Safety Visits in relevant fire and rescue national frameworks. This is crucial to ensure that the frameworks reflect FRS fire prevention activity as FRSs currently understand and deliver it, much of which centres on preventing fires in people’s homes.

Increased fire risk in the home

Most deaths from fire occur in people’s homes. There have been 1,804 fatalities in accidental dwelling fires in England over the last decade, an average of 180 fatalities each year (the total fire-related fatalities in England in 2014/15–2024/25 was 2,699). These deaths are preventable.

Recent technological, societal, demographic, and environmental changes have transformed the risk profile in people’s homes. Rising social deprivation and poor quality housing increase vulnerabilities to fire as more people use alternative heat sources in winter, are unable to afford fire safety equipment, or use cheap or second-hand electrical products that do not meet UK safety standards. The nature of dwelling fires is also changing. Domestic fires are burning hotter and more quickly due to changes in housing construction, the way people live in their homes, and the materials within homes, putting the public and firefighters at risk.[3] For example, the proliferation of lithium-ion batteries, found in many household products, means there are more ignition sources in people’s homes. Lithium-ion battery fires are particularly dangerous as they are instantaneous and explosive in nature, potentially compromising escape routes.

Smoking remains one of the top causes of primary fires in England, and has a disproportionate impact in terms of deaths from fire. Smokers’ materials were the source of ignition for 7.2% of accidental dwelling fires in England over the last decade, but they accounted for 29.2% of fire fatalities during this time (526 fatalities). Illicit smoking products that do not meet relevant safety standards continue to be an issue for FRSs and local trading standards teams. Government analysis suggests that illicit cigarettes made up 10% of cigarettes consumed in the UK in 2023/24. Research has also found that adolescents who use vapes (which contain lithium-ion batteries and are a fire risk) have a similar smoking prevalence to earlier generations, suggesting a possible change to the long-term trend of declining smoking prevalence.

There are also fire risks across the UK’s built environment, as building regulations and statutory guidance have failed to keep pace with new building materials and technology, changing demographics and social expectations, or new legal duties such as the Equality Act 2010. Furthermore, much housing stock is designed for younger families, not older adults who live alone and are more vulnerable to fire.

Sections of the population at a heightened risk of fire – the elderly and people living with disabilities who may find it difficult to evacuate from a fire – are increasing. The number of people aged over 65 in England and Wales increased from 9.2 million in 2011 to 11.1 million in 2021 (18.6% of the total population). It is projected that 26% of the population will be aged 65 and over by 2065, and pensioner poverty is also increasing. The population recorded as having a disability increased from 10.1 million in 2011 to 10.5 million in 2021 (17.6% of the total population). People with restricted mobility due to old age and/or long-term health conditions are more likely to be injured or killed in fires. Yet UK healthcare policy is shifting to care at home and ageing in place models and the provision of technology enabled care (TEC) to vulnerable adults with frailty.[4] The recently published NHS 10 Year Health Plan for England aims to shift care into neighbourhoods, delivering care closer to home and in the home where possible. The plan also emphasised the importance of preventative care. These care approaches bring significant benefits to people’s health, well-being, and quality of life. But they can introduce new fire risks in people’s homes, as homes are a less regulated space where most fire fatalities occur. These fire risks include emollients used to treat skin conditions, medical oxygen equipment, or TEC systems that are not installed correctly. Fire safety must be an integral part of care at home.

As the 2015 Consensus Statement acknowledges, FRS Home Fire Safety Visits are crucial to delivering a health agenda for an ageing population by identifying and mitigating common health and fire risks. Nearly one-third of fire fatalities are people known to health and social care services.[5] But the data needed to inform FRS home fire safety work is often held by other organisations, including GP surgeries, the NHS, local authorities, and other social care partners, and there are barriers to efficient data sharing between services. The sharing of Open Exeter patient data for people aged 65+ between the NHS and FRSs greatly improved the targeting of vulnerable households, and the identification of high-risk hotspots, for FRS home safety prevention work. FRSs would welcome a refresh of the 2015 Exeter information sharing agreement, as well as additional data sharing on frailty and burn injuries. The Government should support the efficient and lawful sharing of relevant data between public services, for example by progressing the development of a risk stratification tool containing fire incident and health and clinical data modelled on the Wales Accord on the Sharing of Personal Information. The Government should also support services with the resource implications of data sharing. Improved data sharing around key health vulnerabilities would enhance FRSs’ risk assessment and targeting of Home Fire Safety Visits as well as referrals to other services, bringing broader benefits to public services. Furthermore, the Government should ensure that NFCC and FRSs are able to access the data submitted to the new Fire and Rescue Data Platform efficiently.

Home fire safety education

Education around various community risks is central to FRS efforts to build safer, healthier, and more resilient communities. Home fire safety education is an important part of this, and incorporates engagement with local schools, arson prevention activities such as youth fire setter schemes, educational work with vulnerable groups, and large-scale public safety awareness campaigns.

Learning about fire risks in the home and what to do in an emergency saves lives. Following a fire in a block of flats in Warrington in June 2025, a resident who was evacuated said, “I knew what to do as we actually get fire leaflets through the door that say exactly what to do in this situation.” Research also suggests educational interventions improve fire safety knowledge, and can reduce fire-setting behaviours where this is a target of the intervention. UK Government analysis following the introduction of the Fire Kills media messaging campaign in the 2000s found that each advertising “burst” saved between four and ten lives (the campaign had more resources in this period than it does currently).

Successful fire safety education should be based on standardised tools and tailored to local demographics and the specific needs of the target audience. This is particularly important when there are very specific risks, for example fire risks for people living with dementia at home who may not consider themselves vulnerable. However, the ability of FRSs to target hard-to-reach populations, broader demographics, or emerging risks is hampered by the limited and ad hoc nature of government funding for fire safety education. Long-term, sustainable investment is crucial.

A strategic, multi-year funding commitment from the UK and devolved governments to support home fire safety education could be used to prevent fires and reduce fire casualties in several ways, including through government-led campaigns or promoting fire safety awareness in the care sector.

Despite its successes, the English public awareness campaign Fire Kills was designed for media consumption habits in the mid-2000s and does not fully reflect the current fire risk landscape or how populations are accessing information. More sustainable funding could be used to update Fire Kills campaign materials, target digital media, and produce resources to address specific risks, and support national campaigns in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Funding could also be used to improve the consistency and reach of FRS education by developing resources that are accessible to broader demographics, expanding and promoting StayWise as a tool for delivering consistent evidence-based safety education, or enabling FRSs to deliver education in more schools in their area. This would bring significant benefits to public safety, not least for people who face barriers in accessing current fire safety advice, for example people with special educational needs, neurodiverse individuals, hard-to-reach populations like traveller communities, people for whom English is not a first language, or people living with dementia.

Longer-term funding could also underpin education targeted at key sectors, for example work to promote the person-centred fire risk assessment process among housing, health, and domiciliary care providers. Staff in these sectors undertake regular visits to vulnerable people’s homes and therefore have thousands of opportunities to identify fire risks in their engagement with residents (the domiciliary care industry alone employs an estimated 809,000 people).[6] Given that around one-third of fire fatalities are people known to health and social care services, systematic adoption of the person-centred fire risk assessment process by companies that regularly engage with vulnerable people could lead to a significant reduction in the number of fire fatalities and injuries. The Government is currently legislating to make the person-centred fire risk assessment process mandatory in certain types of premises. Promoting its adoption in key sectors would reduce fire risk in mid-rise housing, supported housing, and multi-occupied specialised housing, where a significant proportion of residents are at high fire risk.

Smoke alarm provision

Evidence shows that where people receive early warning of a dwelling fire by a smoke alarm the chance of a fatality is greatly reduced. People are 11 times more likely to die in a fire in their home if they do not have a working smoke alarm.

In the 2022–23 English Housing Survey, 93% of households reported at least one working smoke alarm. However, it is possible this is an overestimation. For example, 23% of households in the 2022–23 Survey also reported never having tested their smoke alarm, and are therefore uncertain whether the alarm functions. This is consistent with a 2015 report that found that 22% of households never tested their smoke alarm. Furthermore, data collected in the referrals process for the national online home fire safety check tool found that 50% of all users do not have a working smoke alarm. A significant number of low- and medium-risk households reported no smoke detection (31% as of 2024), and 50% of high-risk households reported no working smoke alarm. Academic research also indicates that smoke alarm ownership is lower among households at a greater fire risk and that the failure to maintain working smoke alarms is not uncommon across the population.[7]

The last large-scale rollout of smoke alarms took place in 2004, with a four-year capital grant of £25 million to English FRSs to establish the home fire risk check programme and install free ten-year smoke alarms, targeting vulnerable households. There was further funding, though a significantly smaller amount, following the introduction of the Smoke and Carbon Monoxide Alarm (England) Regulations 2015 covering private rented homes. Given the limited lifespan of older smoke alarms, many of those fitted in 2004 and 2015 will no longer function. Technological improvements also mean that newer optical smoke alarms provide faster detection and reduce the risk of false alarms.

The Government is committed to improving quality and safety in the rental sector in England by expanding the Decent Home Standards and Awaab’s Law to private rentals, extending local authority enforcement and investigatory powers, and introducing civil penalties for non-compliance. Alongside this welcome action, the Government should ensure that local authorities have sufficient funding and capacity to inspect and enforce compliance with smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide alarm regulations in private and social rentals.

The NFCC Person-Centred Framework for Home Fire Safety Visits sets out criteria for the placement of smoke, heat and carbon monoxide alarms, which should also be fitted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and tested regularly.

Published by NFCC in December 2025

References

- BBC News, ‘Safety leaflets helped me in terrifying flat fire’, 3 June 2025.

- The Centre for Better Ageing, The state of ageing 2025 (2025).

- Clark and J. Smith, ‘Owning and testing smoke alarms: findings from a qualitative study’, Journal of Risk Research, 21,6 (2018), 748–762, (pp. 750–51, 758).

- Department for Communities and Local Government, English Housing Survey: Smoke alarms in English homes, 2014–15 (2016), p. 8.

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities, English Housing Survey 2022–23: Headline report (2023).

- T. Diekman, T.A. Stewart, S.L. Teh, and M.F. Ballesteros, ‘A qualitative evaluation of fire safety education programs for older adults’, Health Promotion Practice, 11.2 (2008), 216–225.

- Evans and M. Wright, Quantitative exploration of the impact of the Fire Kills media campaign (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2009), p. 7.

- The Fire (Scotland) Act 2005, Section 8.

- The Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004, Section 6.

- The Fire and Rescue Services (Northern Ireland) Order 2006, Section 4.

- co.uk, ‘Home care statistics: number of providers, service users and workforce’, 31 March 2025.

- Home Office, An in-depth review of fire-related fatalities and severe casualties in England, 2010/11 to 2018/19 (2023).

- HM Revenue & Customs, Corporate report: Outputs for April 2024 to March 2025 (September 2025).

- James and A. Clark, ‘Fire risk and safety for people living with dementia at home: A narrative review of international literature and case study of fire and rescue services in England’, Dementia, 24.5 (2025), 977–95.

- Jansen, C. Snijders and M. Willemsen, ‘When increasing risk perception does not work. Using behavioral psychology to increase smoke alarm ownership’, Risk Analysis, 44.6 (2023), 1357–1380, (p. 1359).

- Johnston and N. Tyler, ‘The effectiveness of fire safety education interventions for young people who set fires: A systematic review’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 64 (2022), 101743.

- Stephen Kerber, ‘Analysis of changing residential fire dynamics and its implications on firefighter operational timeframes’, Fire Technology, 48 (2012), 865–891.

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Detailed analysis of fires and response times to fires attended by fire and rescue services, England, April 2024 to March 2025 (August 2025).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Fire and rescue incident statistics for England (July 2025), data tables FIRE0202, FIRE0505, FIRE0602, and FIRE0901.

- M. Mongilio et al., ‘Risk of adolescent cigarette use in three UK birth cohorts before and after e-cigarettes’, Tobacco Control (2025).

- NFCC, Person-centred framework guidance for Home Fire Safety Visits (2021).

- NFCC, Fire Risks of Energy Technologies Policy Position Statement (November 2025).

- NHS, Fit for the Future: The 10 year health plan for England (2025), pp. 9–11, 19, 21, 38–39, 57–74.

- NHS England, ‘Improving care for older people’, 2015.

- Local Government Association, ‘Data analysis helps Cheshire Fire and Rescue Service identify most vulnerable’ (1 February 2016).

- Office of National Statistics, Census-based statistics: UK 2021 (2025).

- Public Health England, NHS England, the Chief Fire Officers Association, Age UK, and the Local Government Association, Working together: How health, social care and fire and rescue services can increase their reach, scale and impact through joint working (2015).

- Runefors, N. Johansson, and P. van Hees, ‘The effectiveness of specific fire prevention measures for different populations’, Fire Safety Journal, 91 (2017), 1044–1050.

- Tang, E. Dean, J. Fielding, J. Mann, M. Taylor, G. Devereux, and L. Hindle, ‘Epidemiology of dwelling fires in England 2010–2023’, Fire Safety Journal, 151 (2025), 104294.

- F. Thompson, E.R. Galea, and L.M. Hulse, ‘A review of the literature on human behaviour in dwelling fires’, Safety Science, 109 (2018), 303–312.

- Waring, J. Fielding, and M. Thomas, ‘Examining the effectiveness and economic benefits of home fire safety visits’,Journal of Risk Research, 27.11 (2024), 1341–1357 (pp. 1350–1).

- Waring, S. Giles, P. Carlton, V. Buchanan, ‘Examining the cost-effectiveness of fire service prevention and youth engagement activities’, Fire Safety Journal, 147 (2024), 104186.

- Welsh Government, Inspection of the South Wales Fire and Rescue Service to consider the effectiveness of its response to domestic dwelling fires (2024), pp. 2, 8, 24.

- Christopher Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England, Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2023: Health in an ageing society (2023), pp. 7–8.

[1] Non-fire incidents attended by FRS in England have increased by 69% over the last ten years. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, FIRE0901: Non-fire incidents attended, by type of incident and fire and rescue authority, England (July 2025).

[2] S. Waring, J. Fielding, and M. Thomas, ‘Examining the effectiveness and economic benefits of home fire safety visits’, Journal of Risk Research, 27.11 (2024), 1341–1357 (pp. 1350–1). Waring’s analysis is partly based on research and analysis by the Home Office on the Economic and social cost of fire (2023). See also S. Waring, S. Giles, P. Carlton, V. Buchanan, ‘Examining the cost-effectiveness of fire service prevention and youth engagement activities’, Fire Safety Journal, 147 (2024), 104186.

[3] Modern buildings are designed to be energy efficient and contain heat. In addition, the contents of modern buildings are typically synthetic (plastic) based materials, which burn with a greater intensity and consume twice as much oxygen as traditional materials. Research has found that modern building contents generate a significantly higher heat release rate than traditional materials. Welsh Government, Inspection of the South Wales Fire and Rescue Service to consider the effectiveness of its response to domestic dwelling fires (2024), pp. 2, 8, 24. See also Stephen Kerber, ‘Analysis of changing residential fire dynamics and its implications on firefighter operational timeframes’, Fire Technology, 48 (2012), 865–891.

[4] NHS England, ‘Improving care for older people’, 2015. The Department of Health and Social Care signalled its intention to move care closer to home in a Policy paper on community services published in 2006.

[5] Government research on the profile of fatal and severe casualty victims of fire found that the risk of being a fatal fire victim increased with age, and that the highest proportion of fatal fires were in households containing a single person over pensionable age. Fatal and severe casualty fires also occur more frequently in deprived areas. Though this analysis does not list receipt of health and/or social care packages directly, these can be implied by the proxies of age, living alone, and deprivation. Home Office, An in-depth review of fire-related fatalities and severe casualties in England, 2010/11 to 2018/19 (2023).

[6] Workforce figures from Skills for Care, Social Care Wales, Scottish Social Services Council, and the Northern Ireland Department of Health were collated by homecare.co.uk, ‘Home care statistics: number of providers, service users and workforce’, 31 March 2025.

[7] For an overview of this literature, see A. Clark and J. Smith, ‘Owning and testing smoke alarms: findings from a qualitative study’, Journal of Risk Research, 21,6 (2018), 748–762, (pp. 750–51, 758). Jansen et al.’s study notes that smoke alarm ownership is associated with education, income, home ownership, and non-smokers. P. Jansen, C. Snijders and M. Willemsen, ‘When increasing risk perception does not work. Using behavioral psychology to increase smoke alarm ownership’, Risk Analysis, 44.6 (2023), 1357–1380, (p. 1359). See also English Housing Survey: Smoke alarms in English homes, p. 8.

Home Safety Policy Position Statement (Full Document)

Home Safety Policy Position Statement (PDF)

Equalities Impact Assessment

NFCC Home Safety Policy Position Statement Equalities Impact Assessment