Refer to the Tactical mode section of Incident command: Knowledge, skills and competence and to Risk assessment at an incident in Incident command for further guidance on tactical modes.

The main types of suppression tactics that can be implemented during a wildfire incident are:

- Direct attack

- Indirect attack

- Aerial attack

- A combination of some, or all, of the above

Fire and rescue services should consider providing specialist equipment to personnel for carrying out suppression operations, for example:

- Wildfire-specific hand tools

- Powered hand tools

- Knapsacks

- Drip torches

- Portable pumps

- High pressure suppression systems

- Deep penetration lances

Fire and rescue services should consider making suitable arrangements with other agencies, organisations, land owners or land managers, to provide suitably trained people, equipment and vehicles that can be used to assist with suppression operations. Examples of specialist equipment and vehicles include:

- All-terrain vehicles

- 4×4 vehicles

- Fogging units

- Tractors with mechanical swipes or flails

- Bulldozers

- Excavators

- Water bowsers

Direct attack

Direct attack is where personnel and resources work at, or very close to, the burning edge of the fire. During direct attack, firefighters attack the fire aggressively by using hand tools and beaters and/or by applying water and/or retardants.

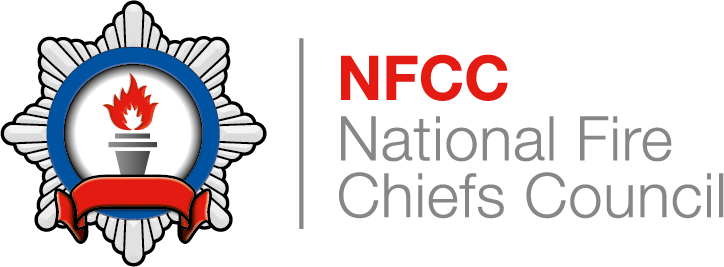

Direct attack can be applied on different parts of the wildfire:

- Flank attack – Attacking the fire along the flank or both flanks simultaneously, usually moving from the tail towards the head

- Head attack – Attacking the head of the fire. This attack method is usually only successful on lower intensity fires and when the flanks of the fire have already been extinguished. This type of attack will be dangerous on moderate to high intensity fires. Crews should never be deployed in front of the fire and/or in unburnt fuel

- Tail attack – Attacking the tail of the fire. A tail attack may sometimes be accompanied by a flank attack, with direct attack crews starting at the tail and moving along the flanks

Figure: Illustration showing the parts of a wildfire

Direct attack using hand tools, beaters and knapsack sprayers can be a very successful suppression tactic when deployed against fires of low or moderate intensities (flame lengths up to 1.5 metres). Applying water and/or foam retardant using pressurised systems may still prove a successful suppression method for fires with flame lengths of 1.5 to 3.5 metres. Personnel working with hand tools, such as beaters, should be withdrawn from the attack until flame lengths are reduced below 1.5 metres.

When using direct attack, personnel and vehicles should always approach and attack the fire from the rear and, where possible, work from an area of fuel that has already been burned. This prevents personnel and vehicles from being deployed in unburnt fuel in front of an advancing fire, which presents a significant hazard. It also helps to reduce the likelihood of personnel or vehicles being outflanked by the wildfire.

If personnel are tasked with using hand tools, particularly edged tools such as pulaskis or rake hoes, care should be taken to ensure that adequate space between personnel is maintained. The spacing required to maintain safety will depend on the type of tool in use and the task being undertaken. It is generally accepted that the safe working distance for swinging tools is twice the length of the tool plus the length of the arm, or approximately three metres; however, this should be risk assessed on an individual basis.

Indirect attack

Indirect attack is where personnel and resources complete suppression activities some distance away from the fire front. This type of attack can be used on flames of any length, but it is often used for high and extreme intensity fires where it is not safe to implement direct attack methods.

Indirect attack methods include creating or using existing firebreaks and fuel breaks as control lines, creating new control lines or using fire as a suppression method.

There is an important distinction between firebreaks and fuel breaks:

- Firebreaks are areas where there is a change or discontinuity in fuel that will reduce the likelihood of combustion, fire intensity and the rate of firespread; they may be suitable control lines

- Fuel breaks are areas where vegetation and all other combustible materials have been removed to expose the mineral soil; they may be constructed and may be suitable control lines

Firebreaks and fuel breaks are two examples of potential control lines. Control lines are constructed or natural barriers, including treated fire edges, which are used to control a fire. They can be constructed manually, mechanically or by applying water or retardants (which are called wet lines).

The minimum recommended width for a control line is 2.5 times the flame length, although it may be necessary or desirable in some circumstances to increase the width of a control line to ensure it is sufficient to contain firespread.

When constructing control lines, it is vital that the rate of firespread is taken into account so that there is sufficient time for personnel to construct the control line and leave the area before the fire arrives. Refer to Firefighting – Firefighting techniques for further information on firebreaks and fuel breaks.

Parallel attack is a specific type of indirect attack where control lines are created along the flanks of the fire towards and around the head of the fire. This suppression method is usually most effective when performed using appropriate vehicles, such as tractors pulling swipes or flails, or bulldozers.

Another indirect attack method is the use of controlled burning. Controlled burns can be lit in advance of the fire to:

- Widen any existing control lines

- Create new control lines

- Burn out fuel ahead of the advancing fire

- Alter fire behaviour

Controlled burning at wildfires can be separated into two distinct methods:

- Defensive burning – lighting a controlled fire to remove fuel in front of an advancing fire, and extinguishing the controlled fire before the wildfire arrives; this method is normally applied some distance from the fire front and should be planned in good time

- Offensive burning – lighting a controlled fire and allowing it to burn into the approaching fire front; this is a higher risk strategy that requires careful assessment and planning

Suitable control mechanisms are required to ensure that controlled burning is completed safely and appropriately at wildfire incidents. Only those personnel that have received appropriate training, and have the relevant experience, should be allowed to use controlled burning as a suppression method.

Aerial attack

Aircraft may be deployed at wildfire incidents to use direct and indirect attack methods.

- Direct aerial attack involves aircraft dropping water or fire retardants onto the burning area

- Indirect aerial attack involves aircraft dropping water or fire retardants in front of the burning area to form control lines or to strengthen existing control lines

Aircraft and drones (unmanned aircraft) may also be used to support other tasks or activities at wildfire incidents. Refer to Inappropriate or uncontrolled use of aircraft for further information about deploying aircraft at wildfire incidents.

Important considerations for developing tactical plans for wildfires

Each type of suppression tactic has relative strengths and weaknesses. The safety and effectiveness of selecting a particular tactic, at a particular time and place, will depend on a number of important factors, including the:

- Current and predicted fire behaviour and firespread (refer to Fire behaviour and Use a wildfire prediction system)

- Scene of operations and terrain

- Reduced visibility

- Resources available

When selecting appropriate suppression tactics, the following should be considered and identified in the tactical plan:

- Windows of opportunity – a period of time, or location on the landscape, when or where it will be particularly beneficial to adopt particular suppression tactics or actions

- Trigger points – a pre-designated point in time, or place, or a change in conditions, when or where tactics will be changed. For example, if a wildfire reaches a particular trigger point on the landscape, the incident commander may decide it is necessary to adopt alternative tactics to maintain safety and effectiveness. To provide another example, if extreme fire behaviour is observed on an area of the incident ground then this may trigger a withdrawal of personnel from this area to a safety zone

- Critical points – a point in time or place, when or where there will be a significant change in firespread, rate of spread and/or fire intensity

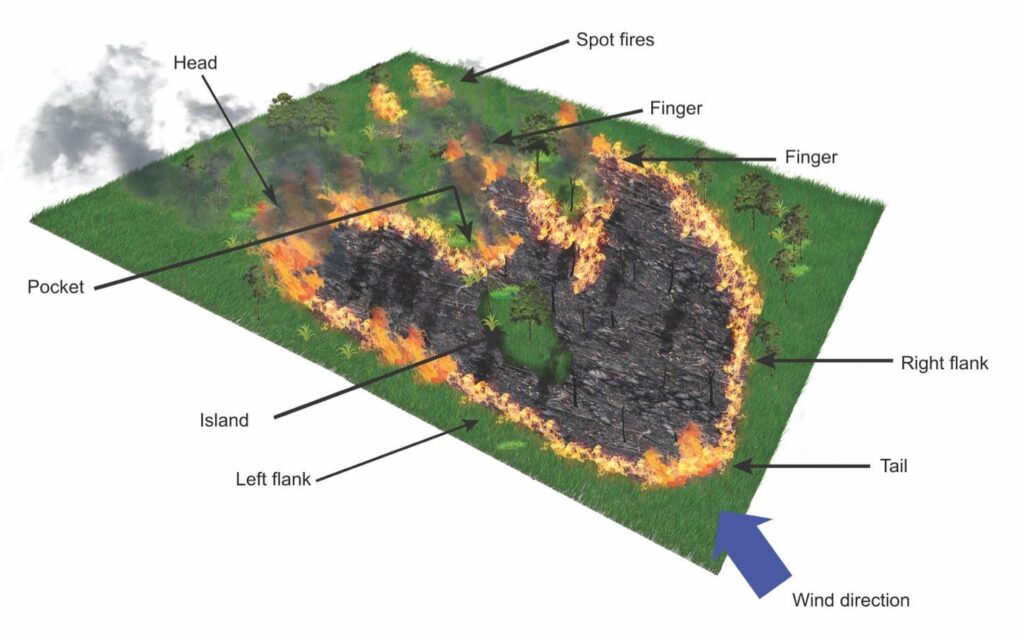

Flame length can be used as a visual indicator of fire intensity and is a useful guide for selecting appropriate suppression tactics and methods. Personnel should be aware that flame length differs from flame height, as explained in the diagram below.

Figure: Illustration showing the angle of the flame and demonstrating the difference between the flame length and height

|

Fire intensity |

Flame length |

Tactic |

Primary suppression methods |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Low |

0 to 0.5 metres |

Direct attack |

|

|

Moderate |

0.5 to 1.5 metres |

Direct attack |

|

|

High |

1.5 to 3.5 metres |

Direct attack |

|

|

Indirect attack |

|

||

|

Extreme |

More than 3.5 metres |

Direct attack |

|

|

Indirect attack |

|

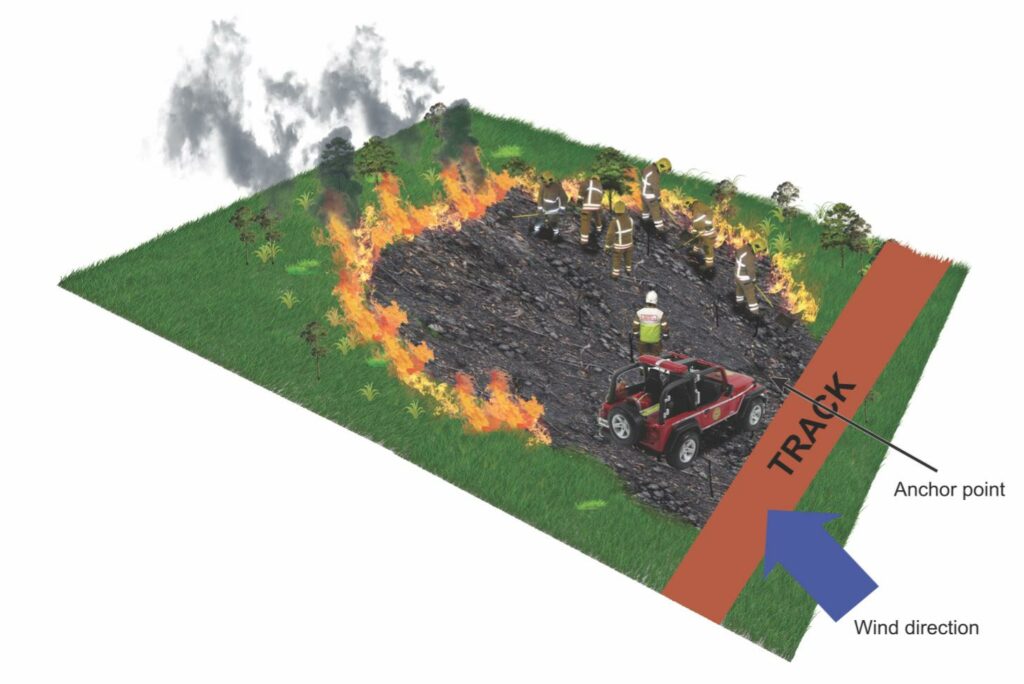

Wherever possible, personnel should commence fire suppression activities from a strong anchor point to help prevent a wildfire escaping and threatening the success of the operation, and/or the safety of personnel. An anchor point is a location on the landscape that can act as a sufficient barrier to firespread. Appropriate anchor points will prevent a fire burning around and outflanking personnel working near the wildfire. Anchor points may need to be strengthened before use or created by hand or machine.

Figure: Illustration showing the use of an anchor point to protect firefighters from being outflanked by a wildfire

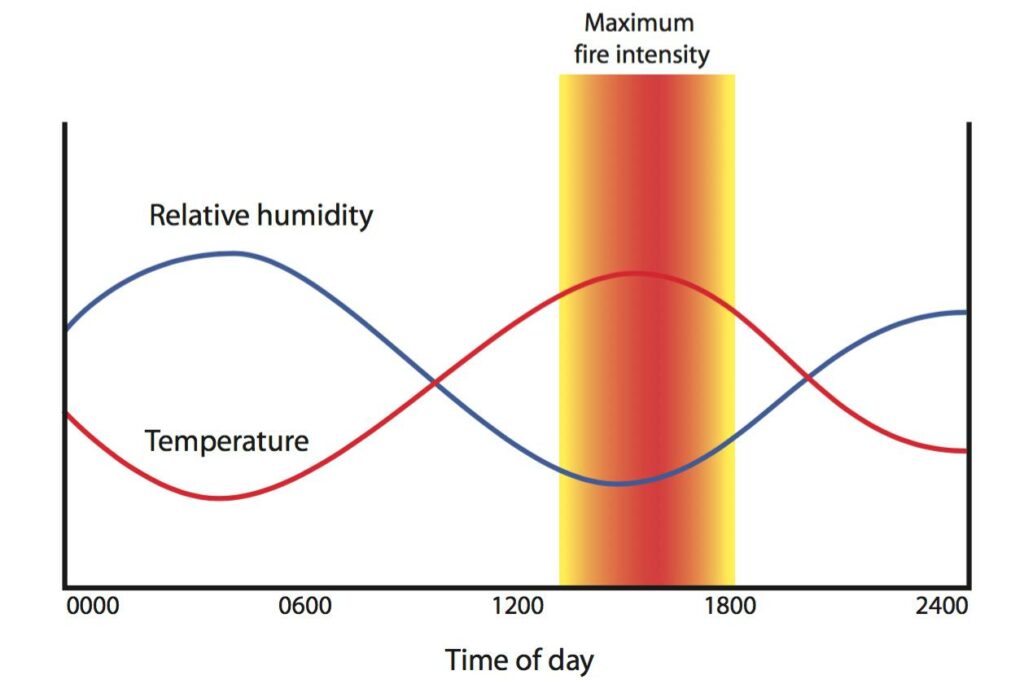

Another important consideration for developing a tactical plan is the time of day. The hours of darkness are generally characterised by cooler temperatures, higher fuel moisture and higher relative humidity levels, all of which can substantially reduce fire intensity. Reductions in fire intensity during the hours of darkness can therefore provide windows of opportunity for suppression. However, there are hazards associated with personnel working at night or during reduced visibility for more information refer to Reduced visibility. Any activities and operations completed during the hours of darkness must be fully risk-assessed, and the hazards must be balanced against the potential benefits.

Figure: Diagram showing the effect of temperature and relative humidity on fire intensity

Refer to the Scottish Government’s Wildfire Operational Guidance for further information about wildfire suppression methods.